Relay Policy Learning:

Solving Long-Horizon Tasks via Imitation and Reinforcement Learning

Abstract

We present relay policy learning, a method for imitation and reinforcement learning that can solve multi-stage, long-horizon robotic tasks. This general and universally-applicable, two-phase approach consists of an imitation learning stage resulting in goal-conditioned hierarchical policies that can be easily improved using fine-tuning via reinforcement learning in the subsequent phase. Our method, while not necessarily perfect at imitation learning, is very amenable to further improvement via environment interaction allowing it to scale to challenging long-horizon tasks. In particular, we simplify the long-horizon policy learning problem by using a novel data-relabeling algorithm for learning goal-conditioned hierarchical policies, where the low-level only acts for a fixed number of steps, regardless of the goal achieved. While we rely on demonstration data to bootstrap policy learning, we do not assume access to demonstrations of specific tasks. Instead, our approach can leverage unstructured and unsegmented demonstrations of semantically meaningful behaviors that are not only less burdensome to provide, but also can greatly facilitate further improvement using reinforcement learning. We demonstrate the effectiveness of our method on a number of multi-stage, long-horizon manipulation tasks in a challenging kitchen simulation environment.

1. Introduction

Recent years have seen reinforcement learning (RL) successfully applied to a number of robotics tasks such as in-hand

manipulation(

We can simplify the above-mentioned problems by utilizing extra supervision in the form of unstructured human demonstrations, in which case the question becomes: how should we best use this kind of demonstration data to make it easier to solve long-horizon robotics tasks?

This question is one focus area of hierarchical imitation learning (HIL), where

solutions(

What are the advantages of using such an algorithm? First, the approach is very general, in that it can be applied to any demonstration data, including easy to provide unsegmented, unstructured and undifferentiated demonstrations of meaningful behaviors. Second, our method does not require any explicit form of skill segmentation or subgoal definition, which otherwise would need to be learned or explicitly provided. Lastly, and most importantly, since our method ensures that every low-level trajectory is goal-conditioned (allowing for a simple reward specification) and of the same, limited length, it is very amenable to reinforcement fine-tuning, which allows for continuous policy improvement. We show that relay policy learning allows us to learn general, hierarchical, goal-conditioned policies that can solve long-horizon manipulation tasks in a challenging kitchen environment in simulation, while significantly outperforming hierarchical RL algorithms and imitation learning algorithms.

2. Preliminaries

Goal-conditioned reinforcement learning: We define to be a finite-horizon Markov

decision process (MDP), where and are state and action spaces, is a transition function,

a reward function. The goal of RL is to find a policy that maximizes expected reward over trajectories

induced by the policy: . To extend RL to multiple tasks,

a goal-conditioned formulation (

Goal-conditioned imitation learning: In typical imitation learning, instead of knowing the reward , the agent has access to demonstrations containing a set of trajectories of state-action pairs . The goal is to learn a policy that imitates the demonstrations. A common approach is to maximize the likelihood of actions in the demonstration, i.e. , referred to as behavior cloning (BC). When there are multiple demonstrated tasks, we consider a goal-conditioned imitation learning setup where the dataset of demonstrations contains sequences that attempt to reach different goals . The objective is to learn a goal-conditioned policy that is able to reach different goals by imitating the demonstrations.

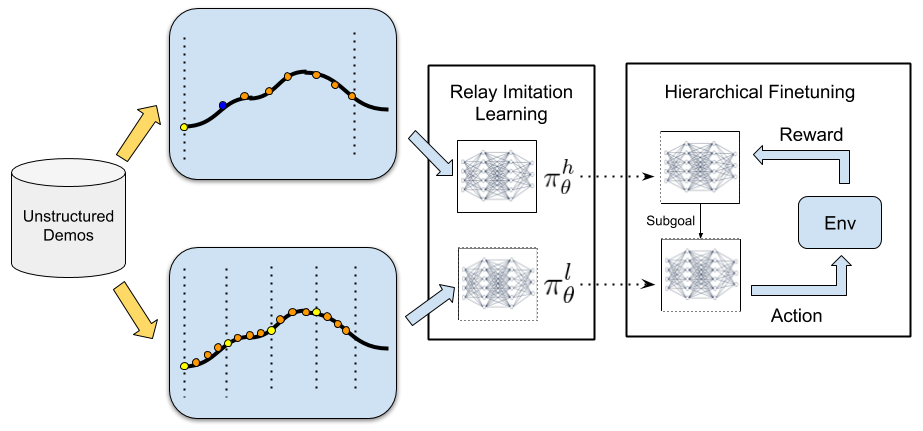

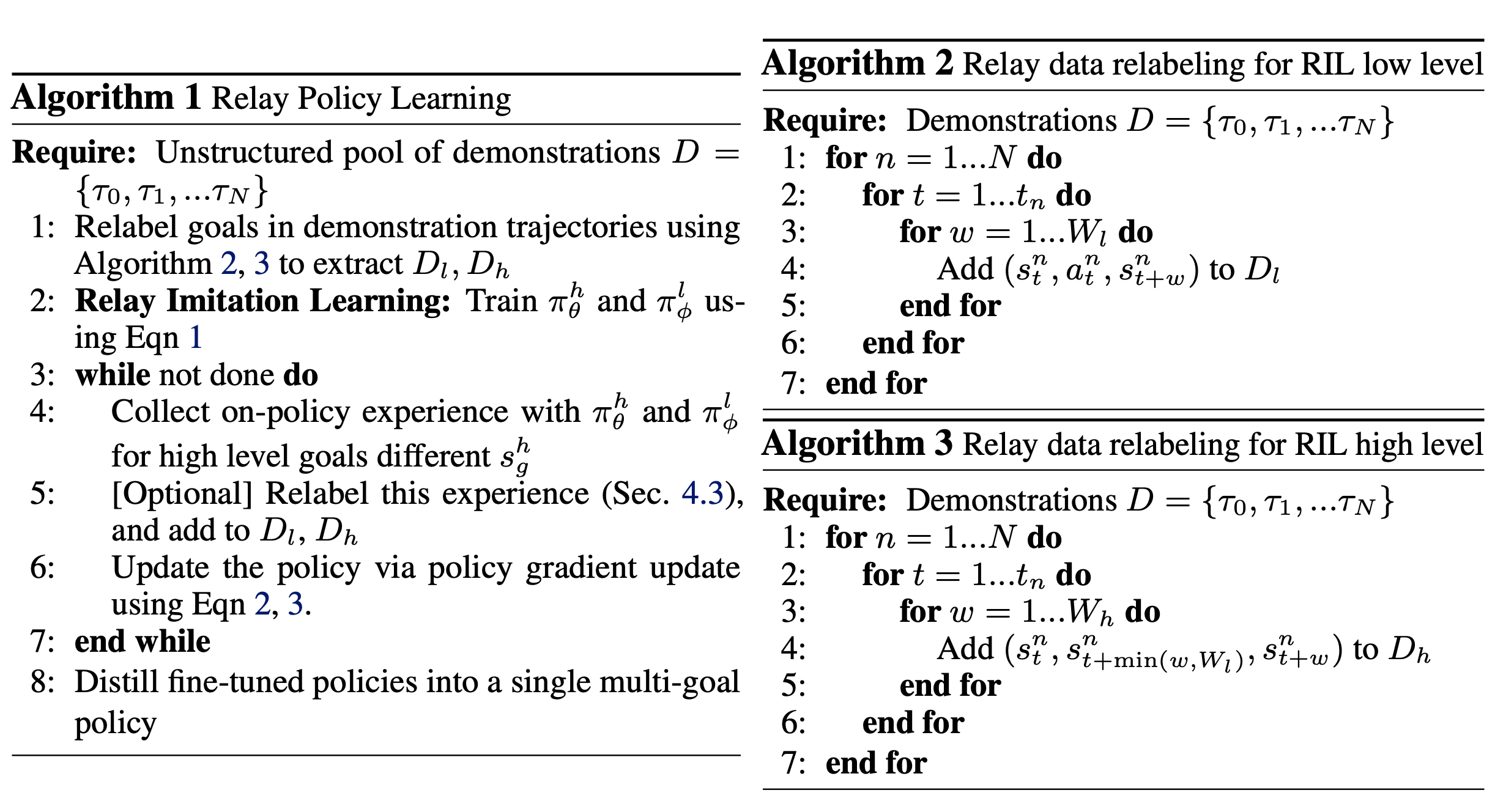

3. Relay Policy Learning

In this section, we describe our proposed relay policy learning (RPL) algorithm, which leverages unstructured demonstrations and reinforcement learning to solve challenging long-horizon tasks. Our approach consists of two phases: relay imitation learning (RIL), followed by relay reinforcement fine-tuning (RRF) described below. While RIL by itself is not able to solve the most challenging tasks that we consider, it provides a very effective initialization for fine-tuning.

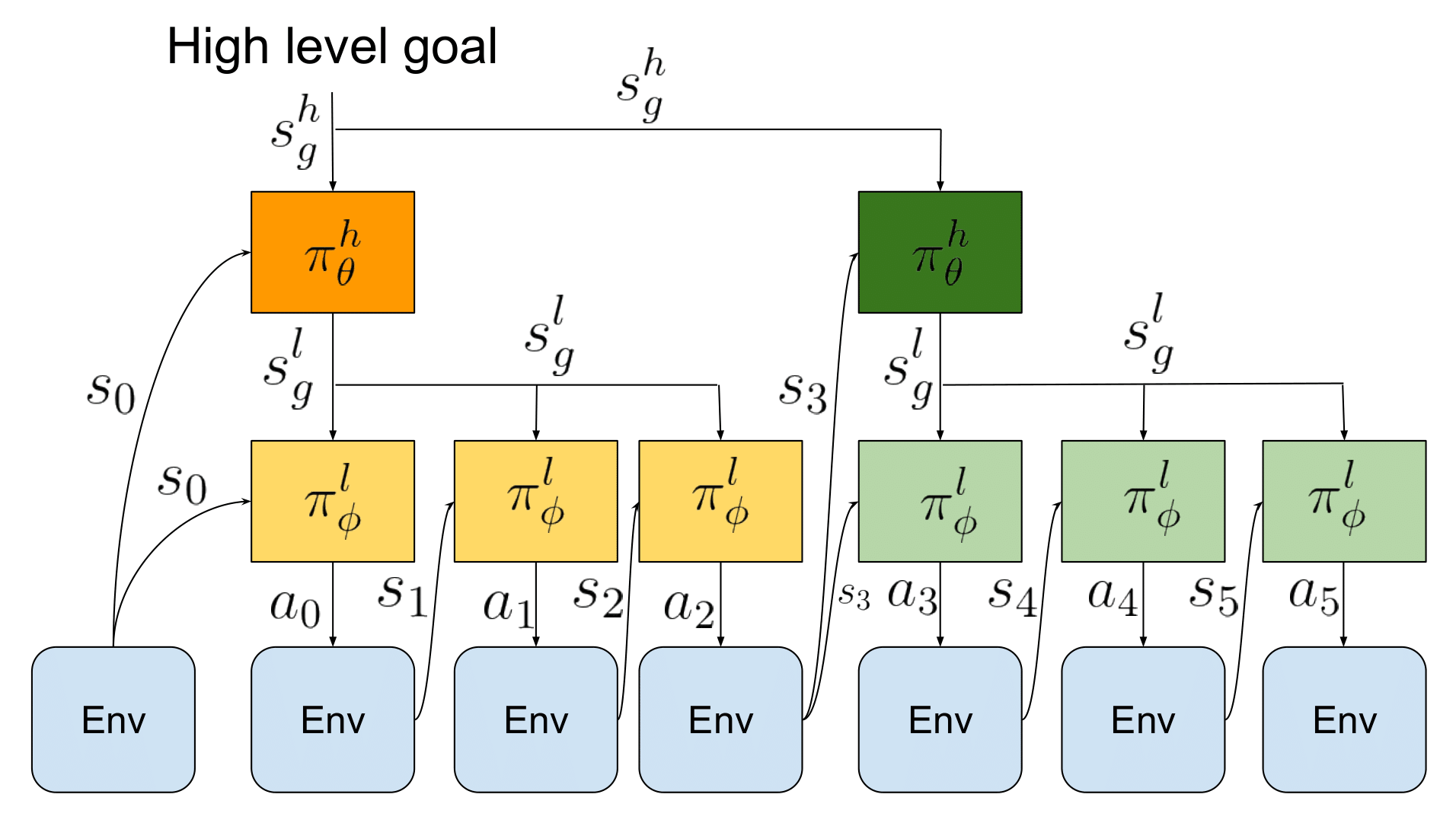

Relay Policy Architecture

We first introduce our bi-level hierarchical policy architecture (shown in Fig 4, which enables us to leverage temporal abstraction. This architecture consists of a high-level goal-setting policy and a low-level subgoal-conditioned policy, which together generate an environment action for a given state. The high-level policy takes the current state and a long-term high-level goal and produces a subgoal which is then ingested by a low-level policy . The low-level policy takes the current state , and the subgoal commanded by the high-level policy and outputs an action , which is executed in the environment.

Importantly, the goal setting policy makes a decision every time steps (set to in our experiments),

with each of its subgoals being kept constant during that period for the low-level policy, while the low-level policy

operates at every single time-step.

This provides temporal abstraction, since the high level policy operates at a coarser resolution than the low-level policy.

This policy architecture, while inspired by goal-conditioned HRL algorithms (

Relay Imitation Learning

Our problem setting assumes access to a pool of unstructured, unlabelled "play" demonstrations

(

We construct the low-level dataset by iterating through the pool of demonstrations and relabeling them using our relay data relabelling algorithm. First, we choose a window size and generate state-goal-action tuples for , by goal-relabeling within a sliding window along the demonstrations, as described in detail below and in Algorithms 2,3. The key idea behind relay data relabeling is to consider all states that are actually reached along a demonstration trajectory within time steps from any state to be goals reachable from the state by executing action . This allows us to label all states along a valid demonstration trajectory as potential goals that are reached from state , when taking action . We repeat this process for all states along all the demonstration trajectories being considered. This procedure ensures that the low-level policy is proficient at reaching a variety of goals from different states, which is crucial when the low-level policy is being commanded potentially different goals generated by the high-level policy.

We employ a similar procedure for the high level, generating the high-level state-goal-action dataset . We start by choosing a high-level window size , which encompasses the high-level goals we would like to eventually reach. We then generate state-goal-action tuples for , via relay data relabeling within the high-level window being considered, as described in Algorithm 2,3. We also label all states along a valid trajectory as potential high-level goals that are reached from state by the high level policy, but we set the high-level action for a goal steps ahead , as choosing a sufficiently distant subgoal as the high-level action.

Given these relay-data-relabeled datasets, we train and by maximizing the likelihood of the actions taken given the corresponding states and goals:

This procedure gives us an initialization for both the low-level and the high-level policies, without the requirement for any explicit goal labeling from a human demonstrator. Relay data relabeling not only allows us to learn hierarchical policies without explicit labels, but also provides algorithmic improvements to imitation learning: (i) it generates more data through the relay-data-relabelling augmentation, and (ii) it improves generalization since it is trained on a large variety of goals.

Relay Reinforcement Fine-tuning

The procedure described in the above section allows us to extract an effective policy initialization via relay imitation learning.

However, this policy is often unable to perform well across all temporally extended tasks, due to the well-known compounding errors stemming

from imitation learning

Given a low-level goal-reaching reward function , we can optimize the low-level policy by simply augmenting the state of the agent with the goal commanded by the high-level policy and then optimizing the policy to effectively reach the commanded goals by maximizing the sum of its rewards. For the high-level policy, given a high-level goal-reaching reward function , we can optimize it by running a similar goal-conditioned policy gradient optimization to maximize the sum of high-level rewards obtained by commanding the current low-level policy.

To effectively incorporate demonstrations into this reinforcement learning procedure, we leverage our method via: (1) initializing both and with the policies learned via RIL, and (2) encouraging policies at both levels to stay close to the behavior shown in the demonstrations. To incorporate (2), we augment the NPG objective with a max-likelihood objective that ensures that policies at both levels take actions that are consistent with the relabeled demonstration pools and from Section 3.2, as described below:

While a related objective has been described in

In addition, since we are learning goal-conditioned policies at both the low and high level, we can leverage relay data relabeling as described before to also enable the use of off-policy data for fine-tuning. Suppose that at a particular iteration , we sampled trajectories according to the scheme proposed in Sec 3.2. While these trajectories did not necessarily reach the goals that were originally commanded, and therefore cannot be considered optimal for those goals, they do end up reaching the actual states visited along the trajectory. Thus, they can be considered as optimal when the goals that they were intended for are relabeled to states along the trajectory via relay data relabeling described in Algorithm 2,3. This scheme generates a low-level dataset and a high level dataset by relabeling the trajectories sampled at iteration . Since these are considered "optimal" for reaching goals along the trajectory, they can be added to the buffer of demonstrations and , thereby contributing to the objective described in the equations above and allowing us to leverage off-policy data during RRF. We experiment with three variants of the fine-tuning update in our experimental evaluation: IRIL-RPL (fine-tuning with equations defined above and iterative relay data relabeling to incorporate off-policy data as described above), DAPG-RPL (fine-tuning the policy with the update above without the off-policy addition) and NPG-RPL (fine-tuning the policy with the update above, without the off-policy addition or the second maximum likelihood term). The overall method is described in Algorithm 1.

As described in

4. Experimental Results

Our experiments aim to answer the following questions: (1) Does RIL improve imitation learning with unstructured and unlabelled demonstrations? (2) Is RIL more amenable to RL fine-tuning than its flat, non-hierarchical alternatives? (3) Can we use RPL to accomplish long-horizon manipulation tasks?

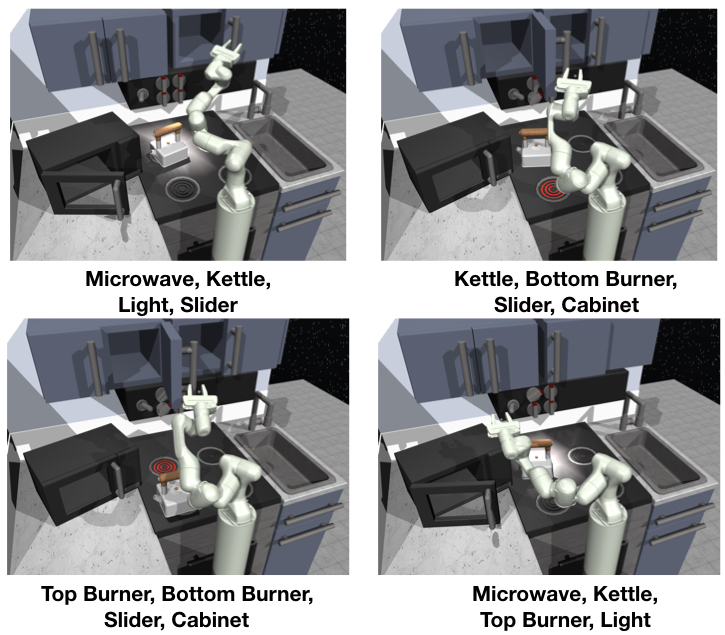

Environment Setup

To evaluate our algorithm, we utilize a challenging robotic manipulation environment modeled in MuJoCo,

shown in Fig 1. The environment consists of a 9 DoF position-controlled Franka robot interacting

with a kitchen scene that includes an openable microwave, four turnable oven burners, an oven light switch, a freely

movable kettle, two hinged cabinets, and a sliding cabinet door. We consider reaching different goals in the environment, as shown in Fig.5, each of which may

require manipulating many different components.

For instance, in Fig.5 (a), the robot must open the microwave, move the kettle, turn on the light,

and slide open the cabinet.

While the goals we consider are temporally extended, the setup is fully general. We collect a set of unstructured and

unsegmented human demonstrations described in Sec 3.2, using the PUPPET MuJoCo VR system (

Evaluation and Comparisons

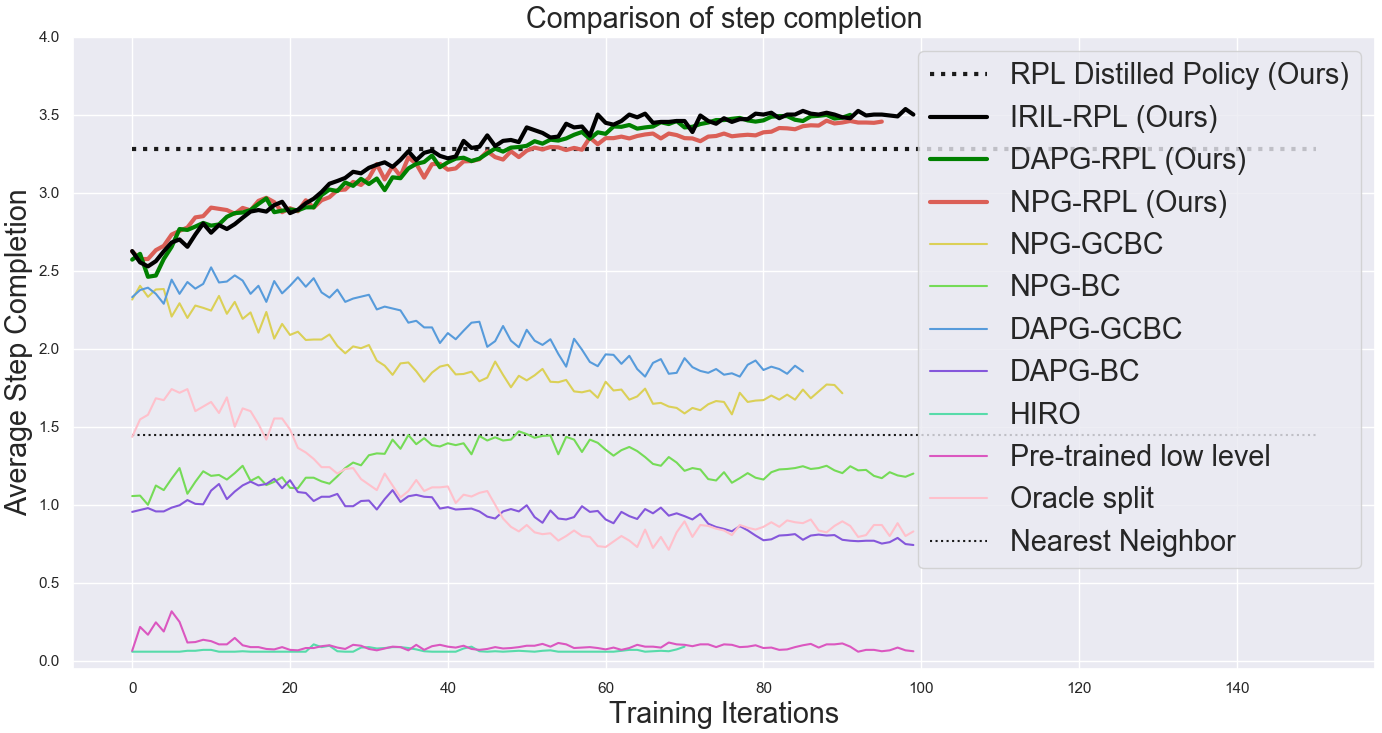

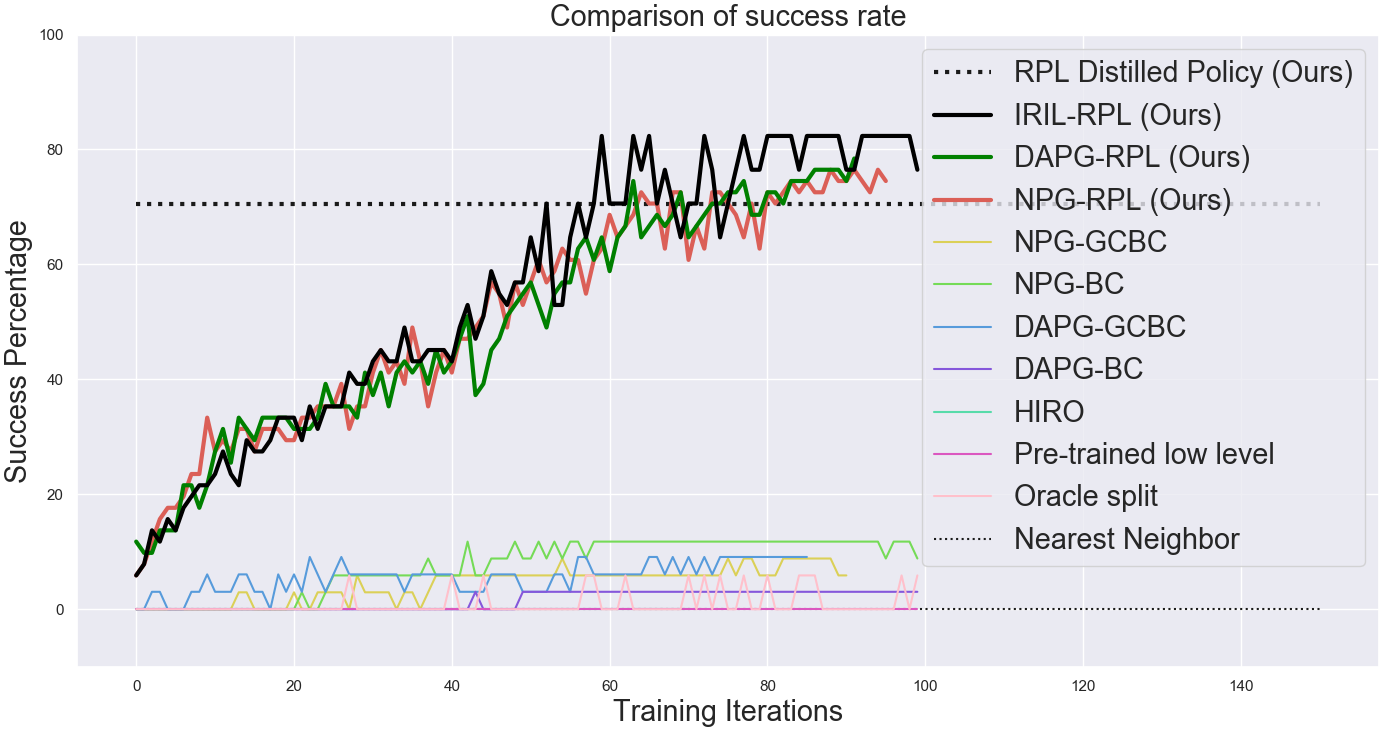

Since each of our tasks consist of compound goals that involve manipulating four elements in the environment, we evaluate

policies based on the number of steps that they complete out of four, which we refer to as step-completion score.

A step is completed when the corresponding element in the scene is moved to within distance of its desired position.

We compare variants of our RPL algorithm to a number of ablations and baselines, including prior algorithms for imitation

learning combined with RL and methods that learn from scratch. Among algorithms which utilize imitation learning combined

with RL, we compare with several methods that utilize flat behavior cloning with additional finetuning. Specifically,

we compare with (1) flat goal-conditioned behavior cloning followed by finetuning (BC), (2) flat goal-conditioned

behavior cloning trained with data relabeling followed by finetuning (GCBC) (

Relay Imitation Learning from Unstructured Demonstrations We start by aiming to understand whether RIL improves imitation learning over standard methods.Specifically, we aim to understand if (1) relay imitation learning in isolation gives us an advantage over flat, goal-conditioned behavior cloning, and (2) whether data relabeling provides us gains over imitation learning without relabeling. In this section, we analyze RIL (Section 3.2) in isolation, with a discussion of relay reinforcement fine-tuning in the following section. We compare the step-wise completion scores averaged over 17 different compound goals with RIL as compared to flat BC variants. We find that, while none of the variants are able to achieve near-perfect completion scores via just imitation, the average stepwise completion score is higher for RIL as compared to both flat variants (see Table 1, first row). Additionally, we find that the flat policy with data augmentation via relabeling performs better than without relabeling. When we analyze the proportion of compound goals that are actually fully achieved (see Table 1, bottom row), RIL shows significant improvement over other methods. This indicates that, even for imitation learning, we see benefits from introducing the simple RIL scheme described in Sec 3.2. This indicates that, even for imitation learning, we see benefits from introducing the simple RIL scheme described in Sec 3.2.

| RIL (Ours) | GCBC with relabeling | GCBC with NO relabeling | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Success Rate | 21.7 | 8.8 | 7.6 |

| Average Step Completion | 2.4 | 2.2 | 1.78 |

Table 1: Comparison of RIL to goal-conditioned behavior cloning with and without relabeling in terms success and step-completion rate averaged across 17 tasks

Relay Reinforcement Fine-tuning of Imitation Learning Policies

Although pure RIL does succeed at times, its performance is still relatively poor. In this section, we study the degree to which RIL-based policies are amenable to further reinforcement fine-tuning. Performing reinforcement fine-tuning individually on 17 different compound goals seen in the demonstrations, we observe a significant improvement in the average success rate and stepwise completion scores over all the baselines when using any of the variants of RPL (see Fig.6). In our experiments, we found that it was sufficient to fine-tune the low-level policy, although we could also fine-tune both levels, at the cost of more non-stationarity. Although the large majority of the benefit is from RRF, we find a very slight additional improvement from the DAPG-RPL and IRIL-RPL schemes, indicating that including the effect of the demonstrations throughout the process possibly helps.

When compared with HRL algorithms that learn from scratch (on-policy HIRO), we observe that RPL is able to learn much faster and reach a much higher success rate, showing the benefit of demonstrations. Additionally, we notice better fine-tuning performance when we compare RPL with flat-policy fine-tuning. This can be attributed to the fact that the credit assignment and reward specification problems are much easier for the relay policies, as compared to fine-tuning flat policies, where a sparse reward is rarely obtained. The RPL method also outperforms the pre-train-low-level baseline, which we hypothesize is because we are not able to search very effectively in the goal space without further guidance. We also see a significant benefit over using the oracle scheme, since the segments become longer making the exploration problem more challenging. The comparison with the nearest neighbor baseline also suggests that there is a significant benefit from actually learning a closed-loop policy rather than using an open-loop policy. While plots in Fig 6. show the average over various goals when fine-tuned individually, we can also distill the fine-tuned policies into a single, multi-task policy, as described earlier, that is able to solve almost all of the compound goals that were fine-tuned. While the success rate drops slightly, this gives us a single multi-task policy that can achieve multiple temporally-extended goals (Fig 6).

A visualization of the different methods is illuminating - we see that RPL policies perform the task much more successfully than baselines and in a more natural way.

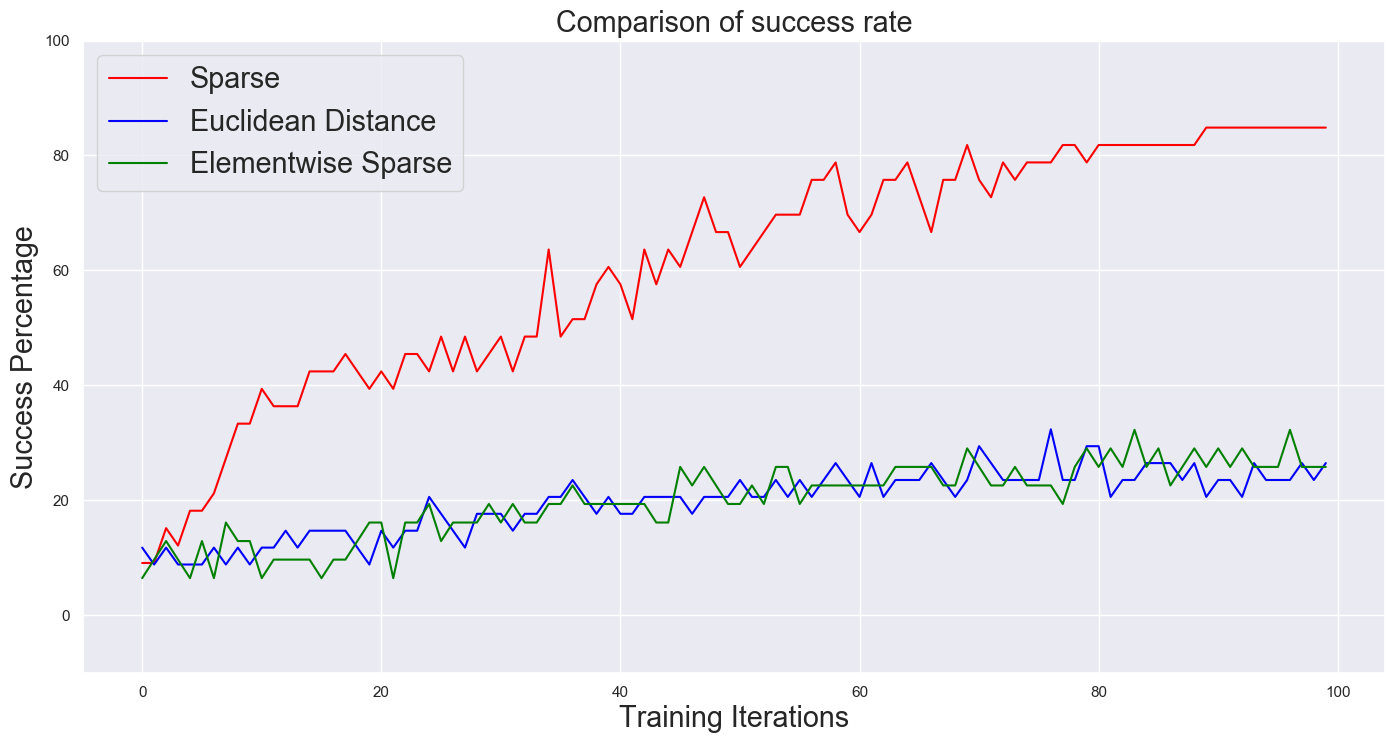

Ablations and Analysis To understand design choices, we consider the role of using different window sizes for RPL as well as the role of reward functions during fine-tuning. In Fig 7 (left), we observe that the window size for RPL plays a major role in algorithm performance. As window size increases, both imitation learning and fine-tuning performance decreases since the behaviors are now more temporally extended.

Next, we consider the role of the chosen reward function in fine-tuning with RRF. We evaluate the relative performance of using different types of rewards for fine-tuning - sparse reward, euclidean distance, element-wise reward. When each is used as a goal conditioned reward for fine-tuning the low-level, sparse reward works much better. This indicates that when exploration is sufficient, sparse reward functions are less prone to local optima than alternatives.

Failure Cases We also visualized some failure cases of the algorithm. We see that the robot completes one or two of the steps and then gets stuck because of difficulties in exploration. This can likely be overcome with more data and better exploration schemes.

5. Related Work

Typical solutions for solving temporally extended tasks have been proposed under the HRL framework (

There has a been a number of hierarchical imitation learning (HIL) approaches (

6. Conclusion

We proposed relay policy learning, a method for solving long-horizon, multi-stage tasks by leveraging unstructured demonstrations to bootstrap a hierarchical learning procedure. We showed that we can learn a single policy capable of achieving multiple compound goals, each requiring temporally extended reasoning. In addition, we demonstrated that RPL significantly outperforms other baselines that utilize hierarchical RL from scratch, as well as imitation learning algorithms.

In future work, we hope to tackle the problem of generalization to longer sequences and study extrapolation beyond the demonstration data. We also hope to extend our method to work with off-policy RL algorithms, so as to further improve data-efficiency and enable real world learning on a physical robot.